Tumours are often stiffer than normal tissues and show abnormally fast metabolism of glucose. It emerges that the link between these two traits involves tension in a network of protein filaments in cells.

Nadia M. E. Ayad.png) &Valerie M. Weaver

&Valerie M. Weaver.png)

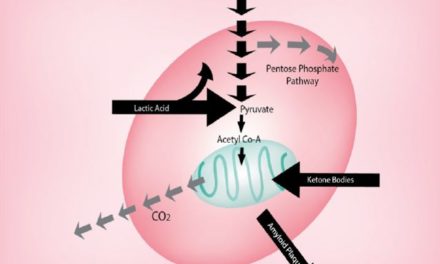

Park et al. set out to examine this process using cells from the lining of the human lung, which are exposed to mechanical changes during breathing. The authors found that, as expected, cells placed on soft substrates in a culture dish did not spread across the dish or assemble actin stress fibres. However, compared with cells placed on stiff substrates, these cells showed a downregulation of several molecules that was consistent with reduced glycolysis.

The enzyme phosphofructokinase (PFK) has a rate-limiting role in glycolysis. The researchers noted that levels of all isoforms of PFK were reduced when the cells were placed on soft substrates. But when PFK levels were increased in these cells, glycolysis was not restored to normal, arguing against the idea that mechanical cues regulate glycolysis by modulating PFK gene transcription.

Instead, Park et al. hypothesized that the loss of PFK on soft substrates was due to protein degradation. A major pathway for this involves enzymes called E3 ubiquitin ligases, which tag proteins with ubiquitin molecules, marking them out for destruction by a molecular machine called the proteasome. In agreement with their prediction, the authors found that, in cells on soft substrates, levels of the PFK isoform PFKP could be restored — and glycolysis enhanced — if they inhibited proteasome activity or mutated lysine amino-acid residues in PFK that are required for ubiquitination.

The group performed database searches to find the E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediates PFKP degradation, and identified TRIM21 as a possible candidate — this was confirmed by experiments in which the gene that encodes TRIM21 was mutated. Next, the authors manipulated levels of myosin or actin and found changes in TRIM21 positioning within the cell. They went on to demonstrate that TRIM21 associates with stress fibres. Their data further suggested that the actin in the cytoskeleton was sequestering TRIM21 and rendering it inactive (and thus maintaining PFKP activity) in response to stiffness outside the cell, promoting glycolysis (Fig. 1). The researchers confirmed this finding by increasing actin-bundle assembly using a mutant form of α-actinin and observing a subsequent increase in TRIM21 levels around actin.

Together, Park and colleagues’ data add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating how the composition of and changes in the ECM can modulate glucose metabolism(5),(6). The data also offer a potential explanation for the aberrant glucose regulation reported in metabolically dysfunctional fatty breast tissue of people who are obese, in which the connective tissue, called the stroma, is often stiff(7). Park and colleagues’ work is consistent with, and extends, another study that has linked cytoskeletal organization to glycolysis(8), as well as work showing how the application of forces between cells can increase cellular metabolism(9).

One of Park and co-workers’ most compelling observations is that tension-mediated sequestration of TRIM21 might explain why tumours exhibit abnormally high levels of glycolysis(10). The group’s unbiased computational assessment showed high levels of PFKP in tissue from people who had lung cancer. The authors engineered their human lung cell line to express some of the cancer-promoting proteins that are frequently overexpressed in lung tumours. PFKP levels were consistently higher in these cells than in the normal lung cells, regardless of the substrate on which they were grown. By contrast, the enzyme’s levels were variable in healthy lung tissue, and the authors’ lung cell line showed varying PFKP levels in response to changes in substrate stiffness.

Unfortunately, such strategies have been disappointing clinically(12). One explanation is that many tumour cells also show increased activity of the RhoGTPase and ROCK enzymes(13),(14), which promote actin-filament assembly, or overexpress oncogenes (which encode cancer-promoting proteins such as Ras and EGFR) that cause elevated actin–myosin tension(13),(14). The cells therefore probably form stress fibres regardless of ECM conditions. Indeed, when Park and colleagues grew lung cancer cells carrying oncogene mutations on soft substrates, they observed that the cells not only maintained prominent actin stress fibres, but also had reduced TRIM21 expression, elevated PFKP levels and high rates of glycolysis.

Finally, the authors showed that the abnormally high glycolysis in their tumour cells could be normalized simply by increasing TRIM21 gene expression. This finding argues that compounds that stimulate protein degradation, augment ligase activity or reduce actin-fibre assembly should similarly normalize tumour glycolysis and hence could be new antitumour therapies. Perhaps the same goal could be accomplished by reducing tumour-cell tension or treating patients with ROCK inhibitors that have already been developed for clinical use — at least in those tumours in which TRIM21 or similar E3 ligases are not mutated (mutations in several E3 ligases have been implicated in either tumour suppression or tumour progression(15)). Indeed, ROCK and EGFR inhibition can reverse the proliferative and invasive traits of 3D in vitro tumour structures called spheroids, and prevent the progression of various cancer types in animal models in vivo(13),(14),(16).

- Butcher, D. T., Alliston, T. & Weaver, V. M. Nature Rev. Cancer 9, 108–122 (2009).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

- Zanotelli, M. R. et al. Mol. Biol. Cell 29, 1–9 (2018).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

- Park, J. S. et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1998-1 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

- Vander Heiden, M. G. & DeBerardinis, R. J. Cell 168, 657–669 (2017).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

- Sullivan, W. J. et al. Cell 175, 117–132 (2018).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

- Bertero, T. et al. Cell Metab. 29, 124–140 (2019).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

- Seo, B. R. et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 301ra130 (2015).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Hu, H. et al. Cell 164, 433–446 (2016).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Bays, J. L., Campbell, H. K., Heidema, C., Sebbagh, M. & DeMali, K. A. Nature Cell Biol. 19, 724–731 (2017).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Pickup, M. W., Mouw, J. K. & Weaver, V. M. EMBO Rep. 15, 1243–1253 (2014).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Burgstaller, G. et al. Eur. Respir. J. 50, 1601805 (2017).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Kai, F., Drain, A. P. & Weaver, V. M. Dev. Cell 49, 332–346 (2019).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

- Samuel, M. S. et al. Cancer Cell 19, 776–791 (2011).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Paszek, M. J. et al. Cancer Cell 8, 241–254 (2005).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Lipkowitz, S. & Weissman, A. M. Nature Rev. Cancer 11, 629–643 (2011).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

-

Laklai, H. et al. Nature Med. 22, 497–505 (2016).

PubMed Article Google Scholar

Dans le diagnostique de problèmes, quand on a du mal à trouver une solution en pensée classique, c’est souvent qu’on a affaire à des causes multiples dont les conséquences sont voisines.

Ici la tension dû à la multiplication cellulaire initiale va aussi provoquer une rupture de membrane basale, avec comme première conséquence une migration hors de l’espace initial (métastases). Cette rupture va alerter les terminaisons nerveuses, qui vont réagir en émettant des hormones comme la noradrénaline pour déclencher un processus de réparation (inflammation/cicatrisation avec multiplication cellulaire via cellules souches). Mais du fait de la pression par la multiplication cellulaire initiale ce processus ne peut aboutir et devient sans fin. Il s’ajoute aux autres causes pour amplifier la progression tumorale.

Pour inhiber cette nouvelle cause, il y a la capsaïcin avec ablation chimique des terminaisons nerveuses ou un beta bloquant générique comme le propranolol pour inhiber les récepteurs de noradrénaline. Voir la publication de Claire MAGNON dans la revue Nature:

https://www.inserm.fr/actualites-et-evenements/actualites/comment-cerveau-participe-cancer

Donc voilà, si on ne traite qu’une cause à la fois, on ne résoudra pas le problème global.

Avec le cancer il faut changer de paradigme et surtout pouvoir espérer un jour cibler uniquement l’espace tumoral.

Car ce qui est actif contre une tumeur l’est souvent aussi contre des organes ou des fonctions vitales.

Traduction: https://translate.google.fr/translate?hl=fr&sl=en&u=https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00314-y&prev=search